A young Chinese scientist, Ye Wenjie is anxiously staring at the stark displays of radio waves in front of her. One is ominously flashing -- “Do not respond. Do not respond. Do not respond.” Her hand hovers nervously over a button. Then she hits it. “Come. We cannot solve our problems on our own. “

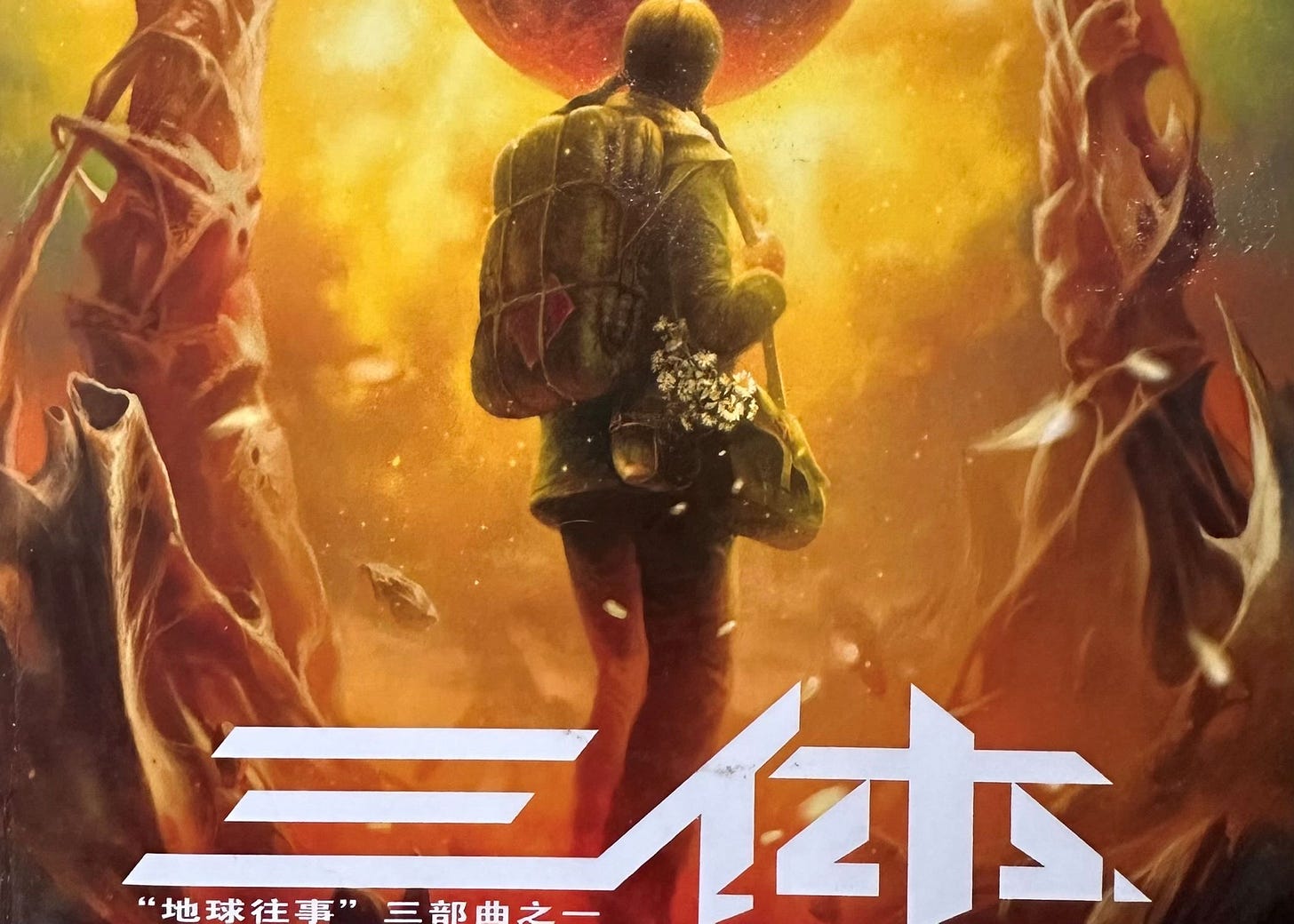

This is the pivotal scene in Netflix’s adaptation of The Three Body Problem, part of Liu Cixin’s sci-fi trilogy Remembrance of Earth’s Past (2008, first published in serialized form in 2006).

A lot of virtual ink has been spilled, critically comparing the Netflix adaption (released March 2024) with the original Chinese trilogy as well as to the 30-episode Chinese TV series (released 2023). But I leave that framework shifting exercise to an ambitious Ph.D. student.

However, the Chinese versions do include a lot more science. This is not surprising given Liu Cixin’s training as an engineer, including work on radio wave technology. While dumbed down in the Netflix series, there are related online discussions describing a real-world classical mechanics ‘three-body problem,’ first explicated by Newton in 1687; that is, the introduction of a third disruptive element to the stable gravitational orbits of two bodies. So how to stabilize or predict those disruptions? While this drives the narrative, I don’t think this is the core problem in Three Body.

The Netflix series also attracted nationalistic outrage on the part of some Chinese netizens that was widely reported by mainstream Western media. The targets of this outrage? Depiction of the deadly human consequences of the Maoist rejection of science -and the brutal violence during the Cultural Revolution under the Gang of Four. But the “scar literature” that slowly emerged in the late seventies in China attests to the society-wide terror and unspeakable abuses committed by propaganda-whipped up masses during that time.

In China as elsewhere, the control of the past controls the present and shapes possible futures.

The incommensurability of translation?

I confess that several years ago, I attempted a ridiculous time-consuming exercise of cross-referencing the English translation with the original Chinese book one of the trilogy. Suffice it to say, I gave up as this attempt was destroying any pleasure, I might derive from reading the book – in any language. Plus, I became painfully aware that my limited Chinese technical vocabulary did not include the universe of foreign tech terms, especially those related to nanotechnology and astrophysics!

I think only a uniquely equipped translator could have successfully taken on the complex multiple levels of world-building of Three Body. But it’s not surprising that Ken Liu (translator of books one and three of Liu Cixin’s trilogy), was able to produce the superb English translation of Three Body that garnered the prestigious Hugo award for best novel in 2015. As an award-winning sci-fi writer in his own right, Ken Liu is also a computer engineer, software developer, and friend of the author. His heart-breakingly beautiful short story, “The Paper Menagerie” is the first work of fiction to win the Nebula, Hugo, and World Fantasy Awards. And he is also a corporate lawyer and high-tech litigator!

At a reading by Ken Liu, I asked him why he changed the flow of the original Chinese chapters in Three Body as it seemed to be a sensationalist way to introduce the series to the English language audience. Chapter one of his English translation opens in 1967 China, but that is chapter 7 of the original Chinese. He responded that Liu Cixin had wanted his original Chinese version to open with the Cultural Revolution chapter. Lurking in the background is the inevitable political navigation by Chinese artists and writers working within a highly regulated media environment. They understand better than anyone how to find the possible openings and how to write between the lines.

So, David Benioff, D. B. Weiss and Alexander Woo, the creators of the Netflix version, had their work cut out for them. In addition to staying respectful to the source text, they had to “translate” for a different audience, adapt the written text to a visual cinematic language, while recognizing the inevitable lost -in -translation process of moving across very different linguistic, historical and cultural contexts.

Frankly, I was skeptical about the addition of new characters (young, brilliant consciously diverse) and the relocation of the current day action to the U.K. in the Netflix series. I thought oh no, not a replay of the debacle of the last season of Game of Thrones. Created by Benioff and Weiss (based upon an adaption of George R.R. Martin’s A Song of Fire and Ice), the last season went increasingly off the rails in terms of narrative and character coherence, clearly the casualty of the GOT TV series outpacing Martin’s writing of the last book of the saga. But surprisingly, I got emotionally invested in the new characters and was deeply moved by the last episode and its honoring of friendship and loyalty.

The real problem –would you press that button?

That moment of choice to invite –or not –an unknown but powerful alien race along with the potential extermination of the human species is a key moment, not only in the Netflix series, but also in the original Chinese novels and the Chinese TV series.

Ye Wenjie, the astrophysicist who chooses to invite the aliens, does so out of profound despair, personal loss, and the death of hope after painfully witnessing the inhuman depths to which human beings are capable of.

Would I press that button? Would you?

In my darkest moments, living in a world engulfed by ‘cultural revolutions’ fueled by ideological extremists bent on holding onto power, no matter the genocidal costs, often feeling helpless in the face of pervasive unforgivable cruelty, I fear I would press that button. In my darkest moments, I think humanity has created its own planet-life extinction events, like the asteroid that wiped out three quarters of animal and plant life 66 million years. I think perhaps humanity has had its moment, but it has failed miserably in stewardship of the planet and all life on it. Perhaps another form of life, one more deserving of this miracle, will emerge from the ashes.

But then –witnessing every day the endless sacrifices of those on the frontlines and the unfathomable kindness of strangers – I move on, humbled. Leonard Cohen sings to me — “there is a crack in everything…that’s how the light shines through.” So, I do the best I can each day to choose the light, to be that crack of light.

"They understand better than anyone how to find the possible openings and how to write between the lines." Dang. This is always fascinating to me, the creation of art under state censorship. I haven't that much experience with the Chinese side but as a Yugoslav/ Serbian girl I spent a LOT of time, in school or otherwise, reading Russian authors who battled the same thing. It is in some ways the pinnacle of human creativity, I think, to dance that dance.

The push the button question reminds me a bit of the current US elections choice. (Pushing the button probably in this scenario being deciding to vote third party and say enough is enough to the two who have competed in failing us worse and worse for long enough). I think yes, I would.

“The Paper Menagerie” is the first work of fiction to win the Nebula, Hugo, and World Fantasy Awards.

That short story is about the dangers of compromising your identity and losing something special in the process. It hits hard for a good number of Asian-Americans, even if they are publicly proud about being inoffensive model minorities that are successful or overrepresented at work.